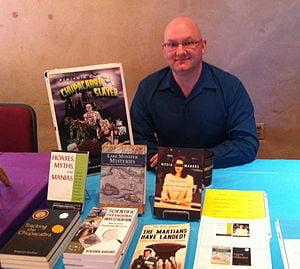

50. Skeptical Inquirer Editor, Ben Radford

Download Audio of This Interview (MP3) (61:10min, 28MB)

[audio:http://content.blubrry.com/skeptiko/skeptiko-2008-08-07-83776.mp3]Alex: Welcome to skeptiko, where we explore controversial science with leading researchers, thinkers, and their critics. I’m your host, Alex Tsakaris.

On today’s show, I have a very interesting interview with Ben Radford, Managing Editor of Skeptical Inquirer Magazine. The interview is almost an hour, so I’m going to jump right into it. But I wanted to let you know that at the end of the interview, I have a couple of comments and clarifications on some of the points we talk about, so you may want to stay with us for that.

We’re joined today by Ben Radford, who is the Managing Editor of Skeptical Inquirer Magazine as you may know. I’m sure you’ve heard of the Magazine. He’s also a columnist forLiveScience.com and the author of three books and hundreds of articles on science, investigating the paranormal and other such topics.

Ben, it’s a great pleasure having you on the show today.

Ben: Good to be on. Thanks.

Alex: You know, as I was researching and trying to get ready for this show, I was trying to gather some background bio information on you, and I didn’t find much. I thought a natural way to start would be for you to tell us a little bit about your bio – maybe some things we don’t know and then, what I think would be particularly interesting is maybe the events or series of events that led you to skepticism and being an advocate of, or having a passion for, investigating paranormal claims from a skeptical perspective.

Ben: Well, I have a background in psychology from the University of New Mexico. That, in a lot of ways, informs me in a lot of my investigations, because many media claims you encounter as an investigator boil down to personal experience – whether it’s a witness sighting on a lake monster or a ghost or what have you , or whether it’s an experience that some people would consider to be psychic in terms of coincidences or precognition or whatever else. Ultimately, a lot of these boil down to psychology, and so that was a little bit of what launched me into doing what I do now.

Basically, I got into skepticism and investigating these sorts of claims when I was a kid, when I was a boy. I would spend many hot summers here in New Mexico where I would go down to the local used book store. I would dump down five dollars in allowance, and I’d buy a bunch of used books. Many of them were these sort of books from the 50s by people like Frank Edwards and Rupert Gould – you know, oddities and stranger than fiction and these sorts of things.

Alex: Right.

Ben: These were books that would have little short chapters about UFOs or monsters, and these were presumably true stories. I mean these were not presented as fictional ghost stories. These were supposedly true accounts. It would say that on the cover. It would say, “stunning and amazing true accounts of the weird and bizarre.” So, I would read these and I’d be getting into them, but then after a while, I would think, hold on here. I’m only hearing one side of this. I only hearing half of the story, because these books would always present always the believer’s side. The only point of view presented was, ooh, this is a mystery…this is unexplained…isn’t this weird, and I never heard anybody saying “Yeah, but hold on. This was explained this way or yeah, but what about this…”

Alex: Right.

Ben: So, that sort of thing – well, hold on here. There’s got to be another side to the story.Then when I was in college, I had won an essay contest, and as part of the prize, I was shipped off to a small town in Utah to present a paper I had written. I happened to be there, and to be honest with you, I was looking for beer.

Alex: [laughter]

Ben: I was in a dry county, so it was not the smartest of moves, but in my search for beer in this dry county in Utah, I came across another used bookstore, and that’s where I found an old copy of Skeptical Inquirer Magazine, of which I am now the Managing Editor. It was a cover issue marked 1986 or something, and on the cover was a piece by James Randi – the Amazing Randi – on Nostradamus.

I read it and I said, “Well, this is interesting. Here is somebody who is presenting a different point of view, who is saying, look, these quatrains that this Frenchman wrote centuries ago – not all of them are what they appear to be.” It gave me a sort of more scientific, skeptical point of view, and from there on, I just got onto the magazine and started doing investigations of my own.

Alex: Fantastic! That’s quite an interesting story, kind of a very organic, naturally grown skepticism that then winds you up at the magazine where you first encountered it. I think that’s pretty cool.

Ben: Yes, it was especially weird – I don’t want to say coincidental, because that frees up all sorts of other implications – but I had bought the magazine, and I was living here in Albuquerque at the time. I showed my Dad and said, “Look, this is an interesting magazine,” and he said, “You know, I think the editor lives here in Albuquerque.” I said, “Nooooo”, and it turns out he was right. The editor, Ken Frazier, was in fact here in Albuquerque. It was sort of strange. Oddly enough, I went up and met him since we lived in the same city, and it just sort of went from there.

Alex: Great. So, in terms of putting together the magazine, you’re obviously there in Albuquerque, but it’s probably like all enterprises now, with online tools and stuff, you can kind of be anywhere and compile everything, huh?

Ben: Yeah, well as Managing Editor I do everything from some copy editing to arranging articles and this and that, and I lived in Buffalo, where the magazine is actually produced, for about then years. Then, I finally got tired of the weather and the economy and other things, and I moved back to the sunny southwest.

Many of the investigations I conducted were in the western New York area, and I’ve also done some in Europe and some here in New Mexico since I’ve been back.

Alex: Great, great. I want to get into some of those investigations, because I think both the process as well as the product and the content that you’ve turned up are really interesting, and I want to dive into that a little bit more. But, one of the things that I exchanged with you in an email, and you got to me right away on, was this idea of dialogue. I think we’re both saying, “Hey, this is great. We’re coming at this from two opposite ends, but we are having this dialogue.” You just don’t see very much of that, or the dialogue that you see is always so bomb-throwing strained that I think it drives a lot of people to polarize the issue.

Why do you think there is such a problem having a dialogue between skeptics and believers, for lack of a better term? And more importantly, why so little collaboration on the research, on the investigations?

Ben: Let me just start by saying that’s exactly right. The lack of meeting of the minds has been a real subject of dismay for me for many years. I’ve found that in my dozen or so years in skepticism investigation that it’s exactly as you said. More often than not you have the believers speaking to the believer camp, the skeptics speaking to the skeptic camp, and rarely is there any sort of interaction. There very rarely any challenges and discussions about it.

Alex: Right.

Ben: And I think that’s very much to the detriment of the investigations. I’ve talked about this many times. For example, a couple of years back I was giving a talk in Idaho at a Bigfoot convention, because that’s one of my specialties. Of course I was the token skeptic[laughter]. Everybody on the panel were these hardcore, long time Bigfoot believers.

I went in there and said, “Look, I’m willing to look at the evidence.” I said, “We have more in common than you think. Unlike the public out there, I take this seriously. I take these investigations seriously. I spend my time, and in many cases lots of money and energy, taking these things seriously – whether it’s ghosts, Bigfoot, lake monsters, psychic powers, crop circles, take your pick. I don’t dismiss them out-of-hand. I don’t say their impossible. I don’t say they’re ridiculous. I say, ‘this is interesting. Let’s check this out.

On that issue alone, we should have common ground, because a lot of the public just think it’s stupid out-of-hand. They say, ‘lake monsters? Psychics? That’s ridiculous. Why would you waste your time?’” My answer is that if I were absolutely certain these things didn’t exist, I wouldn’t waste my time.

I think there are a couple reasons we don’t have better dialogue. One of them is that a lot of people have their reputations staked on a particular position. If you’re someone like Hans Hoser, who’s a big ghost investigator…it’s more difficult for someone like that who’s written a bunch of books on ghosts and the paranormal to say, “Hold on here. Maybe I was wrong about this. Maybe the skeptics have a point that these particular cases that I said were airtight, in fact, aren’t.” There may be some of that on the skeptic side as well, but one of the real problems I find is that the believers – you can take issue with that term. I don’t particularly like that term…

Alex: But what term are we going to use? That’s fine.

Ben: Let’s just go with “believers.” It’s an imprecise and inaccurate term, but it’s functional.So I’ve covered this over and over again. The believers will often ignore the skeptical literature. I’ve seen this over and over. I’ll give you an example. Just two weeks ago, I was in Barnes & Noble, and I noticed there was a recent article on lake monsters. Again, that’s one of my topics of expertise. My last book was on lake monsters.

Alex: Uh-huh.

Ben: I picked it up, and I think, okay, this will be interesting. Again because I’m very familiar with the topic and the individual cases and individual monsters, I was looking to see what this writer had done about including the skeptical point of view. This writer, who’s is actually a fairly well-known cryptozoologist by the name of Karl P.N. Shuker, and other things, had entirely left out any of the research that I and other people have done on lake monsters, and it was amazing to me.

It’s not an issue of pride for me. I don’t care if he cites my work or someone else’s work, but at least be honest about it. Don’t present cases about ghosts or psychics or lake monsters or what have you as if there’s not been any legitimate skeptical criticisms made about them.I’ve seen this over and over and over again, and it’s really frustrating. I don’t know whether it’s just a lack of research, whether they’re just don’t care, or if it really is just mystery-mongering where they say, “Maybe this case was disproved by a skeptical investigation five years ago. I don’t care. I’m going to tell the woo-woo side of it, and no one’s going to know the difference.”

Alex: Right. Oh boy, you brought up so many points that we could probably spend hours talking about, and maybe we’ll spend an hour talking about them because they’re really interesting. I think that one thing is for sure. Every point that you made cuts both ways. I think you acknowledged that almost while you were saying it, and I think we have to acknowledge it, but it doesn’t take away. It doesn’t take away from anything that you’ve said, because I’m sure that it’s all true, that people who are entrenched and who have a reputation invested in having a certain outcome are very reluctant to change their position on things.

Number two – ignoring the other person’s evidence. I mean, that goes on all the time, but it goes on all the time both ways. One of the things that I think is important to acknowledge:there is just this wide diversity of people coming at things from angles that aren’t always the most sincere, aren’t always the most knowledgeable, or aren’t always the most credible.That’s why I think we wind up with all this different stuff.

I don’t know much about the monster thing, but I know the death-bed confession of the Nessie thing with the guy, but it still gets shown. I have a little bit of a sense for your frustration because you’ll still see documentaries, and that picture is still used. Even if the words that overlay it say there is some question now or whatever, why would we use this image if it’s been discredited as a hoax?

Ben: Exactly. If you’ve done basic research or just talked to experts, if they’re legitimate experts, they will acknowledge, “Yes, you know, this image was discredited, proven to be a hoax” or whatever else. Why would you not mention that? It’s misleading to the viewers, and again, part of the question is what is the purpose. Is the purpose just to entertain and put out a good story, or is the purpose to try and find out what’s really happening?

Alex: Right.

Ben: And my position has always been that I like a good story as much as anybody. I like ghost stories. I like tall tales, but don’t call them science. Don’t call them reality if they’re not. That’s one of my big beefs.

I have a little disagreement with you in terms of the ignoring the other side, because what I’ve found – and again, acknowledging that I’m coming from the skeptical point of view…I make no bones about that – but what I’ve found is that the believers far more often ignore the skeptical answers than the skeptics ignore the believer.

Alex: Well, you know the problem with that claim – and that may be true for you and the world that you live in – is that it’s all where you look. One of the biggest complaints I have with the skeptical community is that they often don’t discriminate. Now, I understand that you’re dealing with a lot of claims, and just anecdotally, what you’re saying, there’s the credibility of the people that you were, in passing, talking about are all over the board. One of the things that frustrates me is that skeptics don’t seem to discriminate very well between Uri Geller and Rupert Sheldrake or Dean Raden, so I think people who are doing research, who’ve jumped through the hoops that we normally associate with being good researchers, publishing in peer review journals…a lot of time, skeptics just lump all those people in the same category as some charlatan who’s on TV, preaching some kind of Christian revival stuff with a pick-up in his ear where he can be…

Ben: Right. I agree with that, and that’s exactly right. It goes back to what I was saying before that you have to take these things on a case by case basis. You’re exactly right. Not all people making the claims are the same, and there are people who have tried to take – just for example – prayer studies and bring some science to prayer studies. They say, “Okay, does intercessionary prayer work, yes or no?” And there have been scientific experiments done to address exactly that issue, so there are people who are bringing science to it. I respect that and that should be encouraged.

Of course, as you were saying, there’s also people who will just sort of make these wild claims about, “Well of course prayer works,” and you ask, “You’re saying this based on what?”It’s like “Well…nothing.” So, I agree. There’s a big lumping problem there, and again, we have the same problem with skeptics.

I remember one time a couple years back, I got a phone call out of the blue, at my desk.This woman called me up and said, “Why are you skeptics always so nasty?” I’m like, “I haven’t even had my coffee yet. Who are you?” She’s like, “Well, you know, I was watching a TV show yesterday, and there was a skeptic on there and I don’t remember who he was and he just said everything is bunk and it’s not.” I said, “Hold on here. I don’t know who you’re talking about. You’re not talking about me. You’re not talking about any of the legitimate skeptical investigators that I know.”

You know, I hear this all the time: “The skeptics say…” or “They say…” Who are “they?” Who are these mythical “they” people? If individual skeptics make some debunking claim or counterclaim or whatever else, then do that, but I get this all the time where I’ll read something like, “Skeptics dismiss all UFO sightings as mirages.” What? Where did you get that? That’s not true at all! Or “Skeptics dismiss this…” No, no, no, so the lumping problem goes both ways.

Alex: It does, and I have to tell you that your background is kind of interesting, and in a strange way it kind of mirrors mine in that when I got started looking into skeptical claims, I think I was coming at this from the standpoint of “Wow, I’m hearing these claims of people who are claiming parapsychology claims, and there has to be another side of it” and then digging into the skeptical claims. I’ve got to tell you, I kind of found the opposite of what you found when I really dug into it.

What I decided to do is to only look at what I thought were probably the best paranormal claims. I think Rupert Sheldrake, Dean Radin, Gary Schwartz…people who, at the very least, have very credible academic credentials, have published in peer review journals, and passed the basic requirements of what we’d say are probably good researchers that aren’t making the real obvious mistakes.

Ben: Well, yeah, but you need to be careful, though, because while the people you just mentioned – in general I respect them far more than just someone claiming psychic stuff down on the street – but, when you’re talking about them publishing in peer review journals, that’s true, but they’re not necessarily publishing in that area of expertise. Gary Schwartz, to the best of my knowledge, has never published anything on psi in a reputable peer review journal.

Alex: He has, but hold on. If we get into that, we’re going to miss some of the bigger points that I wanted to make. I think he has and I think I can show you that, but here’s the real point: in that grouping, lumping, that we’re talking about, there are some basic criteria that we can say. We can pick on people and what journals they publish in – which I think is usually a game that’s played incorrectly by skeptics who are unaware of just how many thousands of journals there are and how serious some of these strange-sounding journals are. Take Rupert Sheldrake. I had this discussion at length with somebody, and I said, “Well, he published in Anthrozoos,” and they said, “Anthrozoos??” Well, it turns out Anthrozoos is a very highly respected journal with all the right people on the editorial board and all that. It’s just who knows about these obscure journals unless you’re in animal behavior research?

Ben: Yeah, but is that like, for example, the JSE is, not necessarily? I mean…

Alex: The Journal for Scientific Exploration? Sure, although I think there’s a peer review process, it’s not a peer review process that is in place with a lot of other journals, but the point I was trying to make is that as a first-level cut of what folks we can trust, I think we can look at people’s academic background, their credentials in terms of having a PhD, teaching at an accredited university. It doesn’t automatically mean that we can accept everything that person says, but it does mean we should give them the benefit of the doubt to a certain extent when we look at their data.

Ben: I would agree with that.

Alex: And the real point I was going to make is…the one bit of research that I’ve dug into more than anything else – but it doesn’t relate as much to this show we’re talking about – was the work of Rupert Sheldrake and then Richard Wiseman. What springs to mind when you say that is here’s Richard Wiseman. I don’t want to dissect that whole case in this…

Ben: It’s pretty complicated and involved.

Alex: Well, it really isn’t when you break it down, but I will say this, and I don’t think this is even at question, or controversial: Richard Wiseman is still showing videos of this psychic dog experiment that are completely inaccurate, that were shown on TV, that shows a dog going over to the window. He represents it as a false reading of the owner coming home, and in fact, it’s a cut and paste of a real actual event when the dog was doing what it was supposed to do.

The point is, here is the same kind of thing we’re talking about, in reverse, where a skeptic is making a claim. The claim has been refuted. It’s been beaten down, and yet, it’s still out there, and it’s still being kind of rehashed. That’s true overall with Wiseman’s claim.Wiseman, on my broadcast, has now admitted that his data matches Sheldrake’s, yet when you hear any skeptic talk about – and it’s not “any;” of course there are exceptions – but if you hear any skeptic talk about telepathy and Rupert Sheldrake, they’ll still cite Richard Wiseman’s debunking as somehow proof that it didn’t happen. So, just more evidence that this stuff cuts both ways, and these blind spots that we have are on both sides. The desire to preserve your reputation: it just happens on both sides.

Ben: You know, I can’t speak to what Richard is or isn’t making claims about in terms of cutting and pasting dogs. I’m not familiar with that, so I can’t say that is or isn’t true, and if Richard says that it is, then I’m certainly happy to believe him, but I think the important part here is that we have people who are trying to bring science to it, on both sides. Not that you were characterizing it this way, but I don’t think it’s fair to sort of suggest that Richard’s criticisms of Sheldrake’s experiments, at least in that particular animal behavior case, were some sort of a hatchet job or something. I think, to the best of my knowledge, Richard and his co-authors and others were making a sincere effort to try and understand and figure out what are the different alternative explanations.

Alex: No, it was a hatchet job, but we’ll leave it aside because it would take too long to get into. Let’s talk about more things that you’ve actually researched because it’s not fair to spring that whole thing on you.

Ben: Let me give you another example, then: Gary Schwartz’s afterlife experiments. Gary Schwartz has published a couple of book and studies in which he’s claiming there’s strong evidence for communication with the afterlife, and Ray Hyman, which I’m sure you know, a psychologist at the University of Oregon, an incredible statistician, went through and looked at Schwartz’s claims. He found serious methodological flaws in the analyses and the methodologies.

Alex: Do you remember what those flaws were?

Ben: They were published in Skeptical Inquirer Magazine about five years ago. They’re not on the top of my head, but we had an article on Schwartz’s claims, and then we actually had a rebuttal criticism by Ray Hyman, and then we had Schwartz respond to that. We had it going both ways, and again, my belief is that these are sincere folks.

I don’t think that Gary Schwartz is…I’ve met Gary Schwartz. I like him. He’s a nice guy. We got along. I don’t think he’s trying to pull a fast one. I don’t think he’s trying to deceive anybody. And by his own admission, there are many cases where they’ve said, “Yes, this experiment, like all experiments, wasn’t perfect.” As you know, no experiment is ever perfect. I mean there are always ways it could be improved. You could have tighter protocols.You could add another layer of blinding or what have you.

The same with Ray Hyman. I don’t think Ray Hyman got up in the morning and said, “I’m going to try and destroy Gary Schwartz’s work.” He took a lot of time and effort to try and do a solid, valid analysis and give his critique on them. Another case we did a couple years back was Natasha Demkina, a little girl with x-ray eyes.

Alex: Hold on one second, because before we talk about Natasha, who I don’t know anything about, let me talk about Gary Schwartz, who I know a little bit about.

Ben: Okay.

Alex: Because, number one, I don’t know if you’re aware of this, but we’re replicating that experiment with the folks at the Skeptics Guide to the Universe. We’re going to do an on-air podcast replicating the experiment.

Ben: What experiment are you talking about?

Alex: Well, just the basic medium communication experiment.

Ben: Right, and Schwartz did five or six different ones.

Alex: Right, and the last few that he did was with a woman named Julie Beischel, who, I don’t know if you’re aware, she was at the University of Arizona, and now she’s gone off on her own. You may be aware that, at the end, they continued to improve the protocol and tighten the protocol. At the end, they published in a peer review journal an experiment where they did a triple blind protocol where basically no one knows what anyone is doing.The sitter doesn’t know who the psychic is, and even the intermediary who’s passing the information back and forth doesn’t know either the psychic or the sitter. So, I don’t know if you’ve ever looked at that research, but it does address all the points that were made by Ray Hyman and others.

Ben: Actually it doesn’t, and I do know about the research. One of the issues it doesn’t address is that in many of these cases, the verification of the information is provided by the sitter. That is, this is not information that is supposedly coming from the great beyond that is verified by a third party person. Much of this is information where the medium will say “I’m getting information from, you know, your husband or grandfather or whatever else,” and the information is judged either accurate or inaccurate by the sitter, and there’s an inherent problem right there that has not been addressed by Schwartz’s experiments.

The basic problem with having the sitter verify the information is that it’s subjective. If the person says, “The deceased person is saying there was a problem with his chest,” and the sitter says, “Oh, my Harry who died last year…he died of, you know, pulmonary edema,” so therefore it’s a hit. Well, hold on here. That’s not a valid way to approach the topic.

Alex: I don’t think that you’re quite right in that, and I think that they’ve had intermediaries who have analyzed the information. Moreover, the way that they break down the information – physical description of the person that’s coming through, cause of death, hobbies, and there’s one other category – and they go for very specific information. So, if they died of some kind of chest ailment, yeah you could say it could have been several different chest ailments, but I think if you actually look at the data and the readings that come through, it’s pretty darned specific.

It is also on physical characteristics. If somebody says, “I see a man and he was bald with grey…,” that’s somewhat general, but it also is specific to a certain degree than can be analyzed statistically as to whether it’s accurate. So, I don’t know what you’re saying – whether you throw all that out or how you do that, but I think it’s possible to do an experiment that way, and I really think they’ve come pretty darned close to doing the best possible job you can do.

Ben: I don’t think they’ve really addressed that. For example, what I would like to see in terms of suggestions for people doing this is if you’re going to do this, part of the problem here is that those descriptions you just gave, those can still be vague. Someone says, “The person who’s coming through is a tall man with grey hair.” Well, it turns out when the person died, he was bald, but maybe he lost his hair in the years before his death. Again, this gets back to the problem of the sitter verifying the information, because if the sitter says, “Yes, he had grey hair,” that’s a hit, that’s good information. But, the medium could also say he was bald, in which case the sitter would say, “Well, he had grey hair, but in his last years, he was bald.” So, you can have a medium giving two contradictory pieces of information, both of which would be considered a hit by the sitter.

Alex: Well, it all comes down to how you score it, really, because there’s no way around that problem no matter how you attempt to gather the information from the sitter beforehand.So there are problems there, but there are also…like I say, in the details of the reading, I think you can also see, if we’re objective about it, that there’s some way to get at the statistical significance of the reading.

Ben: Well what I think we should do, for example…again, part of the problem is a lot of these descriptions are generic: “I see a tall man.” Okay, I’ll tell you what. Use subjects who do not fit what most people would consider to be a normal profile. So, have a subject who maybe lost his legs during the war, and presuming no one would know this, see if the medium says, “Yes, the person is coming through. He doesn’t have any legs.” Or a birth defect that would be obvious that isn’t just a tall man with glasses. I guess my point is there should be enough variation in the subjects such that meaningful distinctions can be made, and if the person was a dwarf, or the person…I don’t know, but there are ways to do this where a generic description of you know, a tall man with dark hair would not fit.

Alex: Well, I think I’m going to have many more shows on that, including having some cold readings from some folks who claim they can do a cold reading and get just as good of results. I just don’t think you’ve looked at the actual readings that they’ve received. Like I’ve said, I’ve interviewed Julie Beischel a couple times on the show, and I understand her methodology as she described it to me.

Another thing is that they get names many times, which – of course there’s some names that are more common than others – but it’s pretty easy to put a statistical significance on someone’s name or even a letter of someone’s name. Folks who are able to do that time and time again offer pretty compelling evidence that can’t be easily explained.

Ben: Part of my problem with the whole notion of mediumistic communication is that a lot of the stuff is so mundane. Okay, let’s just say, for example, you do have a medium who can say, “Yes, I’m getting a message from the other side, and it’s a person, and this is his name, and he loves you.” Okay, what value is that? Why don’t we see information coming out that neither the medium nor the sitter knows? I haven’t seen that.

Alex: But then, as far as the medium coming through and saying, “I love you,” that would never be scored on any of the experiments that Schwartz or Beischel did. It always had to be specific information. They never scored “I love you” or “You’re feeling good…”

Ben: No, no, but that’s very typical. I’ve attended dozens or hundreds of psychic readings and séances in the world, and that sort of stuff is very typical. I mean I have yet – and if you can point me to any example of this, I’ll be happy to follow it up and write it down and say I was wrong – but I have yet to find a case either in psi research generally or in Gary Schwartz’s experiments specifically that have information that neither the medium nor the sitter knew – that is, new information, not something the sitter retrofitted into something that the medium said.

Alex: I’ve got some of that, so I’ll get back to you on that. We’ll do that. I mean I will follow up on that with you, and I’ll ask Julie Beischel, and maybe we’ll have a conference broadcast.

Ben: I mean, just to give a quick example, why is it that we don’t have reports where a grown daughter whose parents died, and they can’t find the keys to the safe deposit box where the deed to the house is, and the answer, and the medium sits down and the medium says, “The key you’re looking for is behind the fourth step in your old house on the lake,” and someone goes there and finds it. That’s never happened.

Alex: [laughter] I think it has happened, but more importantly, let me say something.

Ben: Well, where are they?

Alex: We’re going to follow up on that. I’m going to follow up on that. I don’t know the readings as well as Julie Beischel, but I’ll get you that. More importantly, the question that you asked is a really tricky question. I think so many times when I encounter skeptics who are really interested in the science or the research, like you obviously are – they quickly switch into this mode which I think is a dangerous mode, and that is presupposing that we have some understanding of how these things operate, when we don’t. We can’t really ask the question “why doesn’t this come through” or “why doesn’t that come through.” All we can ask is, “is there any information coming through.”

Ben: Hold on here. Of course there’s presuppositions here. That’s what the experiment is about.

Alex: The experiment is about finding out whether there’s a phenomena at all, rather than questioning why the phenomena works the way that it does.

Ben: Right, but the point that I’m making is that Gary Schwartz and other psi researchers…just to develop a methodology for studying these things, they’re making assumptions all over the place.

Alex: No, they don’t really have to. They’re making…

Ben: For example, they’re making assumptions that the medium will contact the spirit of a dead person. That’s the basic assumption.

Alex: Well, that’s the question, right? What I’m saying is…let’s not get too far afield. All I’m saying is that I don’t think you can jump four research questions ahead and say, “Why is the nature of the communication this way versus this way” before you’ve identified whether or not there’s a phenomena at all occurring.

Ben: I agree.

Alex: But that’s kind of what you do when you say, “Why doesn’t anyone do this…” or you’ll hear some people say, like you did, “Why don’t they come through and just talk to me,” or something like this. You’ll talk to mediums who’ll say, “Well, that’s not the way it is. I’m getting images and all the rest of that.” You don’t want to take that on face value either and say that just because some medium says that this is how they’re getting the information, that’s how all information is getting through.

I think what these folks are doing – folks like Julie Beischel and Gary Schwartz – is the very beginning, first stages of research in the way that you have to do them: asking the fundamental questions and examining whether or not there’s a phenomena that’s there.What seems to be a frustration on the part of them is that, even when they come up with that first set of data, there’s this wave of resistance to ever get to those follow-on questions and really understand the nature of this work: statistically which works better, this kind of communication versus this kind of communication, how long the person has passed, all these other questions.

Ben: That’s true, and I would absolutely agree with you that there is a resistance to that, but the resistance comes from the fact that many of these methodologies are flawed. Many of these studies have mistakes in them. I’m not saying all of them are, and some experiments are better than others. If they’re good scientists, if they’re trying to do good science, then people like Schwarz and Radin and other people like that will acknowledge and say, “Yes, the criticisms of this case are correct. This could be done better. This could be done on a different way.”

Alex: Well, I’ll tell you what, Ben. Bone up on the Julie Beischel experiment that she did, the triple blind protocol. I’ll have you on with her, and we’ll talk through that, because I think her understanding of that and of the criticisms and how they’ve been addressed is very different from yours. I think it would be extremely interesting. She’s a very nice person to talk to. She’s not an edgy person. She’s very down to earth, and I think it would be a great opportunity to hash that out, and for me to learn something.

Ben: You know, part of the problem is that skeptics are sort of bottom line folks. It’s like, here’s the bottom line: if this evidence is out there, if these things are real, then why aren’t other things happening? For example, unsolved crimes are a perfect example. People claim that one common definition of a ghost is someone whose murder has been unavenged. Well, in America and all over the world, there are literally tens and hundreds of thousands of unsolved murders. Now, presumably, if all it takes to solve a crime is to contact the spirit of the dead person and say, “Who killed you, where’s your body, what are the circumstances,” that’s all it takes.

Alex: But that’s back to the last point. You were about to say you can’t figure out…well, I’m a believer. I’m going to hold onto that title. But, I would not go so far as to say what you just said. I don’t understand the nature of the spirit world and how it works and all the rest of that.

You know, you just waded into a subject that I did want to talk about today in this whole idea of psychic detectives, because I’ve read many of your articles, and you’re obviously a very talented writer, and you do a good job of summing up these cases. You’re not flying off the handle in a really incendiary way, but I do feel like a lot of times you pick on cases that have failed and make the case that that somehow proves something. To me it’s like you’re trying to be the Better Business Bureau for psychics and say that some of these psychics are not as good as other ones or some of them are outright fraud. Fine, but as I was reading, I was thinking, “Gosh, why hasn’t he looked at the best cases.”

Let me give you an example. Here’s someone I’ve actually spoken with, a psychic I’ve spoken with. Nancy Orlen Weber is her name, and she was on the Psychic Detective show. I go to her website in preparation for this interview we are doing here, because I’ve seen your cases where you’ve said that some of these psychics that appear on TV never solve any cases, and all the rest of that. You go right to her website, and you read her letters of reference from detectives, detectives who have been in the New Jersey State Police for 25 years and say, “Yeah, I’ve worked with her on all these cases and she really helped.” “Yeah, I spoke with these other investigators who worked on murder cases with her. She did a really good job.She received a letter of commendation.”

It’s like there’s this total disconnect. Do we really care that there’s all these failures? Or do we care that the phenomena does seem to happen at some times with some people to the extent that it’s proven beyond a doubt to the very folks who are very skeptical to begin with?When you talk about a detective on the New Jersey Police – these people are not easily going to go in and dupe with some tall story. Where’s the investigation on the best cases?

Ben: Well, there’s a couple answers to that. First of all, in my investigation of psychic detectives – or anything else for that matter – I cannot and will never prove that psychic powers don’t exist. I cannot and will never prove that Bigfoot or ESP or whatever…that’s not provable. All I can do is I can say, “We’ve looked into this. This is what’s been found, and in these cases, the evidence is right there. Look for yourself. This is not true.”

Look at the case, for example, of Allison DuBois, who was not only one of the subjects for Gary Schwartz, but was also the basis for the TV show, Medium. She claimed that she had actually solved cases for the Texas Rangers and the Glendale Police Department, and I called the Texas Rangers and I called the Glendale Police Department, and they said she hadn’t done that. Now, there’s some investigation right there. You have a high-profile medium who is making claims that she solved cases. All it takes is a couple phone calls to find out that’s not true.

Now, in terms of the best cases, part of the problem is that – and I get this all the time – people will say, “Here’s the best case. Look into this.” So, I look into it, or Joe Nickell or someone else will look into it, and we solve the case, and someone says, “Oh no, this is the best case over here.” The problem is there’s always somebody new claiming that, “No, no, no. Maybe you explained those, but this, this is the best case.” It’s a never-ending battle because every time you explain something, there’s always some other case somewhere else, some other psychic who claims this.

Alex: Okay. I understand. I understand how that could be frustrating. But, I do have to kind of call into question the basic methodology in terms of you were calling it the methodology of the investigation. I’ve just given you a specific case where I wouldn’t rely on the medium. If I were doing an investigation, I wouldn’t start with the medium. I’d start with the police. It’s like the show, Psychic Detectives, and we can take the cases that Nancy Weber’s been on, and take the police that have gone on the record and said, “This person did help us in the investigation and found all this information that we couldn’t have found any other way, and came up with this stuff totally out of the blue,” and ask them if there’s any misrepresentation – which we know sometimes happens in the media – of what you said.

Ben: There’s a problem there, though. The problem is that instead of doing investigating, you’re taking another person’s words for her claims. That’s not an investigation.

Alex: I’m saying as a starting point…

Ben: For example, I’ve talked to police captains who believe in psychics and believe in psychic detectives. I mean I’ve interviewed them. I know that they exist. There’s a hidden assumption in what you’re saying that all police and detectives are hardboiled, hardcore skeptics, and would necessarily be able to verify or not verify a psychic’s help.

Alex: Hold on. Let me interject here. All you have to do is watch that old show Psychic Detectives, or take any of these cases that are documented here, and you’ll find plenty of detectives who say – the story gets repeated so many times it’s like they’re reading it off a script – “Hey, I was completely skeptical. I never trusted these people, and then I got in this case. They found the body; they found the car; they found this…,” specific things. Now, to me, that’s the place to start an investigation.

Ben: You’re right, and I’ve done that.

Alex: Tell me where you’ve done that, where you’ve started with someone who’s…

Ben: Okay, the case of Charles Capel, a guy who went missing. If you do a Google search for my name, Benjamin Radford, plus Charles Capel, you’ll find my investigation into the case of Charles Capel who was an old man who wandered off. There was a well-known psychic detective – I forget which one it was, probably Noreen Renier – who said that she had solved the case, and when you go back and look at it, she didn’t solve the case at all. Part of the problem is…

Alex: But did the police say she had solved the case?

Ben: No, she did.

Alex: That was my point again. Why not start with a case where the police have said they psychic solved the case?

Ben: Actually, in that particular case, the detective did say that, in fact. His name is Sergeant Squance, and I interviewed Sergeant Squance and I said, “You know, you’re quoted in this article as saying that this psychic helped in the investigation.” He said, “Yes.” I said, “What exactly do you mean by that?” He said, “Well, when we found the body, some of the stuff she said was right.” I was like, “Oh, oh, oh, oh hold on here.” There’s red flags all over the place. That is not “helping them in the investigation.”

If that’s the criterion for solving a case – and that’s what this police detective said; I think he was a Sergeant – that was the criterion that he was saying led him to think that she had helped solve the case. I said, “Well, who found the body.” “Well, it was found by a passerby.”So, the psychic did not locate the body. If that’s your criterion, then any psychic who says, “Well, the body will be found partially clothed, somewhere near water” is always right, because most bodies are found partially clothed and somewhere near water. If that’s your criterion, then sure, psychic detectives are always right. But, if you criterion is does this psychic provide specific information that leads people to the body – that leads people to the body…not afterwards some parts of it are found true like “Oh there was a white house somewhere nearby,” or “There was a rock nearby” or whatever else – that’s not psychic information.

Alex: Fair enough, fair enough. But, hold on, because we’re going to have another follow-up on this one, too, because this psychic detective topic is something that’s always been of great interest to me, and I’ve never been motivated to devote a whole broadcast to it.

Ben: Okay, tell you what we’ll do. Why don’t we do this: you find the best case you can find.Just look at all the psychics you want. Figure out one, and pick the one case that you think is airtight and give it to me, and I’ll get back to you in a couple of months, and we’ll see what we find.

Alex: Fair enough. That’s a challenge that I can live with. And I’ll tell you what. We’ve taken about an hour of your time, and we’re really going to try and cut it short. You know, we’re going to talk again, because it’s been a real pleasure to talk with you. It’s been a great exchange and I totally respect where you’re coming from. There’s a lot of follow-on work we can do, so we’re going to follow up with Julie Beischel, and we’re going to talk some more about the psychic medium – both the demonstration that we’re doing with the folks at theSkeptics’ Guide and the past work that’s been done – and then we’re going to do this psychic detective thing too. I think it will be really, really interesting to follow up with that.

Ben: Absolutely. I’m looking forward to it. And, I’m hoping – let’s just set it out – if I’m wrong, and sure enough this airtight best case you can find really does show solid good evidence for psychic powers, I’ll be happy to admit that. I would expect that if I can show serious flaws and errors and mistaken assumptions and bad logic, etc., then you would say, “Yes, the best case that I found turns out not to be so good.”

Alex: I will admit that publicly. If you want me to stand on a chair while I’m doing it and videotape myself, I’ll do that too.

Ben: It should be fine. Fair enough [laughter].

Alex: Well, it was great talking to you, Ben, and anything coming up for you that we should be looking out for?

Ben: Let’s see. I was recently on an episode of Monster Quest on the History Channel on my investigation into Chupa Cabra. I have an article coming out in Fortean Times, the British magazine of mysterious things where I investigated a haunted house in Jamaica, and if anyone’s interested, they can check out my books and stuff on RadfordBooks.com.

Alex: Great! And don’t you have some kind of board game I was reading about? Is that still something you’re doing.

Ben: Yeah, to be honest with you, that’s what’s been eating up most of my time and energy over the last six months. I invented a board game called Playing Gods, and it’s sort of like theological RISK, where two to five players each play a different god and they try to take over the world to their own religions and either kill off other gods followers with locusts or plagues or natural disasters or convert them.

Alex: I saw the god characters on the website – the cartoons – and they look really well done, so I’m sure it’s entertaining.

Ben: Yeah, its’ fun.

Alex: Well, thanks again, and we’ll be talking to you soon.

Ben: Good enough. Bye.

***********************

Alex: Well, I wanted to thank Ben again for joining me today on skeptiko. I really did enjoy the interview, and I think we managed to find a lot of common ground, particularly in our desire to further investigate some of these claims, and really get to the bottom of them, which is the goal of skeptiko after all.

The one point I did want to clarify a little bit – because I glossed over it in the interests of time during the interview – and that’s this point about Richard Wiseman and his use of this video that isn’t very accurate. A few months ago, when I was really in full swing investigating Dr. Wiseman’s claims against Rupert Sheldrake, and I did a number of shows on that, I dug up this video that really, I think, speaks to some of the points that Ben and I were talking about.

Now, this video has been used over and over again by Dr. Richard Wiseman in these talks he gives about the debunking that he did of the Dogs That Know experiment. There’s two really, really big problems with this video. The first is that the video portrays something that didn’t happen, so the video shows the dog, JT, repeatedly going to the window, and the voice-over suggests that this is a false positive by the dog. That is, the dog is sensing that the owner is coming home, and the owner really isn’t coming home.

There’s two big problems with this. The first, and most important, is that the data inside the experiment doesn’t support the claim that he’s making, right? So Richard Wiseman has come on the skeptiko show and said that his data matches Rupert Sheldrake’s, which means that the dog really is somehow sensing that the owner is coming home. If you remember correctly, the actual statistics on this are quite lopsided. I think in the case of Richard Wiseman, if my memory’s correct, about 78% of the time, while the owner’s coming home, the dog is correctly responding. So, to suggest in this video that this shows this repeated pattern of the dog incorrectly sensing that the owner is coming home is a complete misrepresentation of the facts as he now understands them.

But, the second part of the problem with that particular video clip is that the video they’re using isn’t really of the dog misinterpreting the owners coming home, so what they did was sliced and diced a little bit of video where JT is going to the window and sensing that the owner is coming home, but they used a video of JT correctly sensing that the owner is coming home. Yet, they use a voice-over that suggests that this is a case of the dog repeatedly going to the window when the owner isn’t really coming home.

As kind of skeptical folklore goes, this gets repeated over and over and over again. You may recall that when James Randi was on this show, he repeated this folklore by saying, “I’ve talked to Wiseman about that dog, and he said that the dog went to the window all the time.” Again, look at the data. The data suggests otherwise, and Wiseman has now acknowledged that the data isn’t the problem with the experiment. So that’s one part of the problem. You can excuse that away however you want. Of course, video and TV production has a lot of flaws to it, and people are interested in portraying the story rather than getting the real science correct.

Here’s the second problem, and I got this directly from Dr. Sheldrake when I spoke with him. Several years ago, Dr. Sheldrake pointed this out to Richard Wiseman. He said, “Hey, you know what? You’re using this video, and this video isn’t really correct.” This was before Wiseman admitted that his data matches, so his was point was just that, “Look, you’re using video of JT correctly sensing the owner coming home, and it’s being portrayed as an incorrect false positive.” And Wiseman said, “Oh yeah, gee, I’m sorry. You know those TV producers put things together the wrong way. Sorry about that.” But he’s continued to use the video for years after that. Now, this is just the kind of skeptical blind spot that Ben and I were talking about.

Ben, of course, sees it on the side of believers, and I, of course, see it on the side of skeptics.What I wanted to do here is make clear just how these little burrs in the saddle of believers fester, and why they fester…because there are cases like this that are just clearly outside the bounds of what should be done in good science and what should be done in good faith in terms of a coming together of skeptics and believers, and it doesn’t always happen that way.

Hopefully, Ben and I can kind of transcend this and get to a point where there really is a true collaboration, there really is an open-mindedness on both sides. I certainly hope we can get there. I hope we can get there with the Skeptics’ Guide folks if we’re able to move forward with the medium research. I think we will. I did manage to get a very brief chat in with Dr. Novella, and we’re kind of targeting September as a time for doing that work, so we’re going to look forward to that.

Okay, thanks for listening. If you need any information on our previous shows or would like to dig through the archives, please visit the skeptiko website. That’s skeptiko.com. You can also find links to our forum and an email link where you can reach me and a bunch of other interesting information there.

That’s going to do it for this show. Until next time, bye for now.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS